I did not know what to expect walking into the judging floor at HackNC 2025. I had read about the event beforehand, knew it was the largest hackathon in the Southeast, knew it was student-run out of UNC Chapel Hill, knew it draws over seven hundred participants. But knowing a number and standing inside the room where those seven hundred people have been working through the night are two very different experiences.

The venue was a gymnasium. Long wooden floors, high ceilings, round tables packed end to end with laptops, tangled charger cables, half-eaten snacks, and teams of two, three, four, five students who had collectively not slept since Friday evening. The energy in that room was something specific. Not loud exactly, but alive. The particular hum of people who are tired and proud at the same time, who stayed up for something they care about.

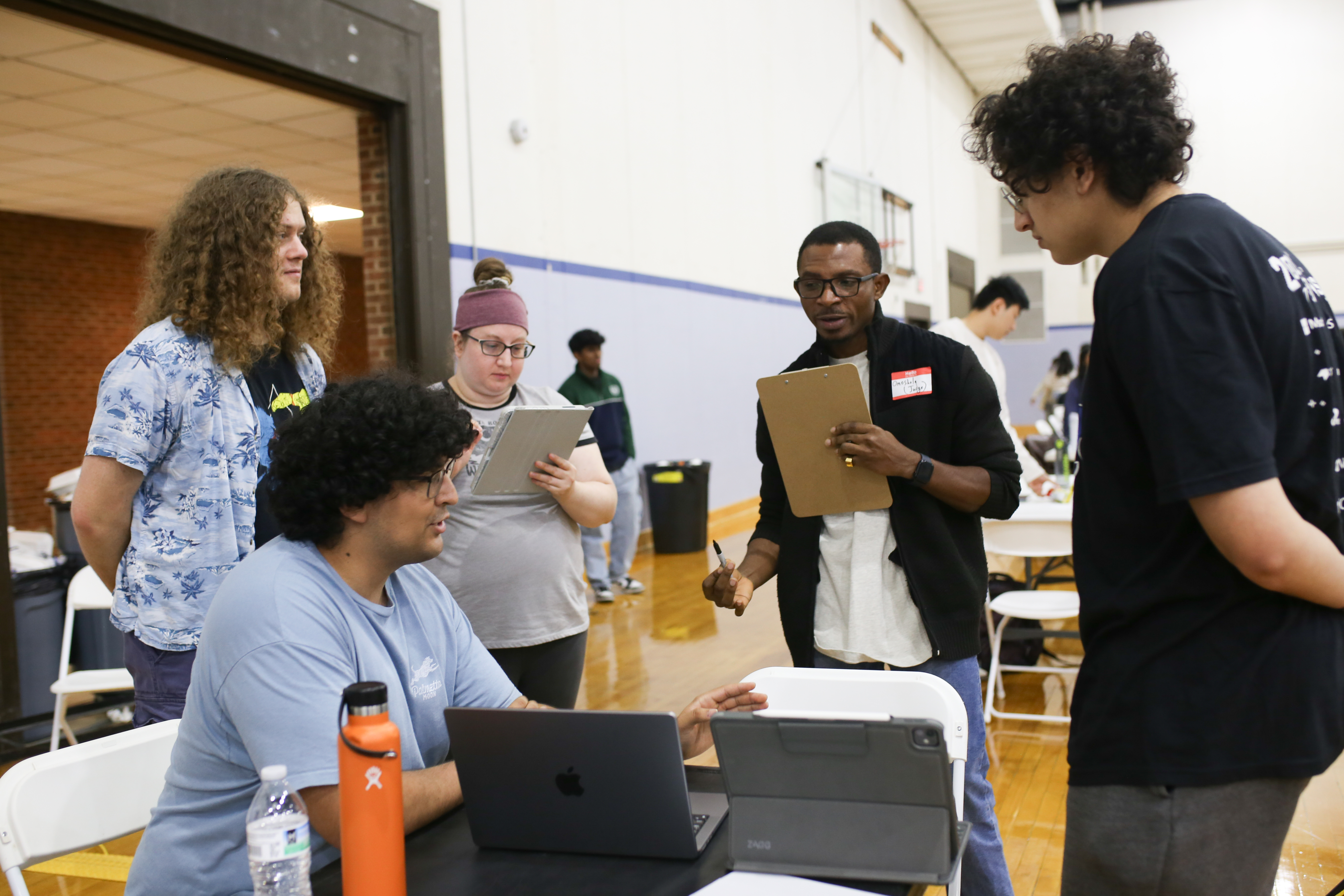

I picked up my judging clipboard, found my starting assignment, and got to work.

The rotation

The judging process at HackNC is a rotation. You move from table to table, team to team, a few minutes at each station. Teams pitch their project, show the demo, answer questions. Then you move on. It sounds mechanical described that way but it does not feel that way when you are doing it. Every table is a different world. Some teams are polished, smooth delivery, clearly rehearsed. Others are still fixing a bug as you walk up, half apologizing, half explaining what went wrong and how they solved it at two in the morning. Both kinds are impressive. The polished ones have built something complete. The ones still fixing bugs have built something while solving problems nobody planned for, which is really what a hackathon is testing.

The range of projects was remarkable. Some teams built tools for environmental monitoring. Some tackled mental health and wellness. Some went purely for technical ambition, compiler work, network infrastructure, things that do not have a flashy demo but represent serious engineering. A few teams built games, which always draws a crowd during judging because everyone wants a turn. The breadth of what people chose to care about enough to build something in twenty-four hours tells you a lot about the state of student technical culture right now. It is in very good shape.

What HackNC gets right

Before I get to the project I have been thinking about ever since I left Chapel Hill, I want to say something about the organizers and the student team that pulled this off.

Running a seven-hundred-person event is genuinely hard. Coordinating sponsors, managing check-in, scheduling workshops, running the judging process across dozens of tables and dozens of judges, feeding everyone, keeping the energy up through a full twenty-four hours. The HackNC team did all of this without it showing. The logistics were invisible, which is the best thing you can say about event logistics. When things are invisible it means everything went right. That does not happen by accident. It takes months of planning and a team of people who are themselves students, doing this on top of everything else they carry.

So thank you to HackNC, to the UNC Department of Computer Science, to the School of Data Science and Society, and to every student volunteer who made October 10 through 12 happen. The sponsors, Principal, Pearson, John Deere, Wells Fargo, Infosys, CapTech, Bandwidth, Cisco, they showed up for a reason. Events like this are how the next generation of technical talent gets built.

The table I will not forget

I have to talk about them.

There were five of them at the table. I remember the energy before they even started the demo, focused, a little nervous the way you are when you know what you built matters. They had a laptop open and a webcam positioned in front of a chair.

They built a communication system for bedridden individuals using eye blinks.

Let me explain what that means in practice. If you cannot move your hands, if you cannot speak, if your entire voluntary motor control has been reduced to the movement of your eyelids, this system gives you language back. You look at the camera. You blink. Slow blink, fast blink, blink duration, blink patterns. The system reads those patterns and translates them into letters, words, sentences. You can compose a message. You can text your family. You can send an emergency alert. You can say anything you would say if you could speak, just through the movement of your eyes.

They asked me to simulate it.

I sat down in front of the webcam and they walked me through the blink vocabulary. Slow close, quick open. Hold. Two short blinks. I was constructing words. Clumsily at first, the way you are clumsy with any new language, but constructing them. And what hit me, sitting there pretending to be someone who could not use their hands, was not the technology. The technology is impressive. It was the realization that for some people, this is not a simulation. For someone with ALS, or locked-in syndrome, or severe post-stroke paralysis, this is the gap between silence and speech. Between isolation and connection. Between lying there unable to ask for help and being able to press a button with your eyes and call someone.

That is what five students built in twenty-four hours.

Why this is bigger than a hackathon

I have been in technology long enough to know when something is genuinely new. Assistive communication technology exists, but it tends to be expensive, proprietary, and slow to reach the people who need it. Eye-tracking hardware for communication can cost thousands of dollars. This team built a proof of concept using a webcam and pattern recognition that any family with a laptop could theoretically run.

The real-world need is not abstract. ALS affects tens of thousands of people in the United States alone. Locked-in syndrome, which leaves patients cognitively intact but unable to move, is one of the most devastating outcomes of stroke and certain neurological conditions. The ability to communicate, to maintain a voice, to stay connected to the people you love, is not a nice-to-have. It is fundamental to dignity and to care.

These five students solved something that hospitals and assistive technology companies are actively working on and have not fully cracked. They did it in one night.

A message to those five

If you are reading this, I want you to hear this clearly.

Protect your work before you do anything else with it. Before you make the GitHub repository public, before you pitch it to a company, before you post it on social media, file a provisional patent application. It is not expensive and it is not complicated at the student level, and it buys you twelve months of protection while you figure out what comes next. Your university’s technology transfer office can help you start that process. Many schools also have resources through the law school or the entrepreneurship center.

The idea is proven. The technical approach works. The people who need it are real and they exist right now. Do not let this stay a weekend project. You have the beginning of something that could genuinely change how people live. Take it seriously. Build on it. Find a researcher, a mentor, a clinician who works with the population you are serving. Get feedback from the people this technology is for.

I have no stake in what you decide to do next. I am just a judge who sat in front of your camera for five minutes and walked away thinking about you for weeks. That is the version of impact you should be building toward.

Walking out of UNC

I left Chapel Hill that evening with that particular kind of tiredness that comes from being genuinely engaged for hours. Not the drain of a long meeting. The specific depletion of paying close attention to a lot of interesting things, which is a good kind of tired.

What stayed with me was not just one project. It was the aggregate of what I saw. Seven hundred students who chose to spend their weekend building. The problems they chose to care about. The technical ambition across fields. The fact that the Research Triangle is producing this kind of talent at this scale and these students are still in school.

HackNC reminded me of something I think gets lost in conversations about the future of technology. The future is already being made. Not in the labs of large corporations, not in the hands of the people who have already made it. It is being made by students who stayed up all night in a gymnasium in Chapel Hill because they had an idea and twenty-four hours to see if they could pull it off.

I will be back next year. I hope those five are there to tell me what they did with what they built.